Throughout history, art has dabbled in the unsettling spectacle of female rage. From the baroque portrayals of the Maenads tearing Orpheus limb from limb, and the depiction of Timoclea of Thebes in Elisabetta Sirani’s “Timoclea Killing Her Rapist” (1659), to modern artists like Yuko Tatshushima, whose haunting paintings, gave birth to several online creepypastas as they often featured women, desolated with righteous anger radiating on their faces. This potent emotion has left its mark on cultural consciousness. The same visceral energy translates to the works of contemporary artist Aleksandra Waliszewska, albeit in a more cryptic and unnerving way. Her art channels a primal, feral rage, coated in such grotesquerie that it leaves a lingering unease.

Born in 1976 in Warsaw, Aleksandra comes from a lineage of artists; her mother and grandmother were both painters and sculptors. Notably, her grandmother, Anna Dębska, was a significant 20th-century sculptor known for her monumental depictions of animals, particularly goats and horses, which served as a source of inspiration for Aleksandra’s work. Upon graduating from the city’s Academy of Fine Arts, she quickly established herself as a leading figure in the Polish new art scene with over 20 solo exhibitions, the prestigious Arco Madrid Grand Prix, and the EXIT magazine award.

The Polish painter seems to maintain an air of mystery around her paintings. Most of the work is untitled, and she isn’t interested in explaining the intended meaning behind any of them, as she believes art is subjective to the viewer, and once explained, the charm is lost.

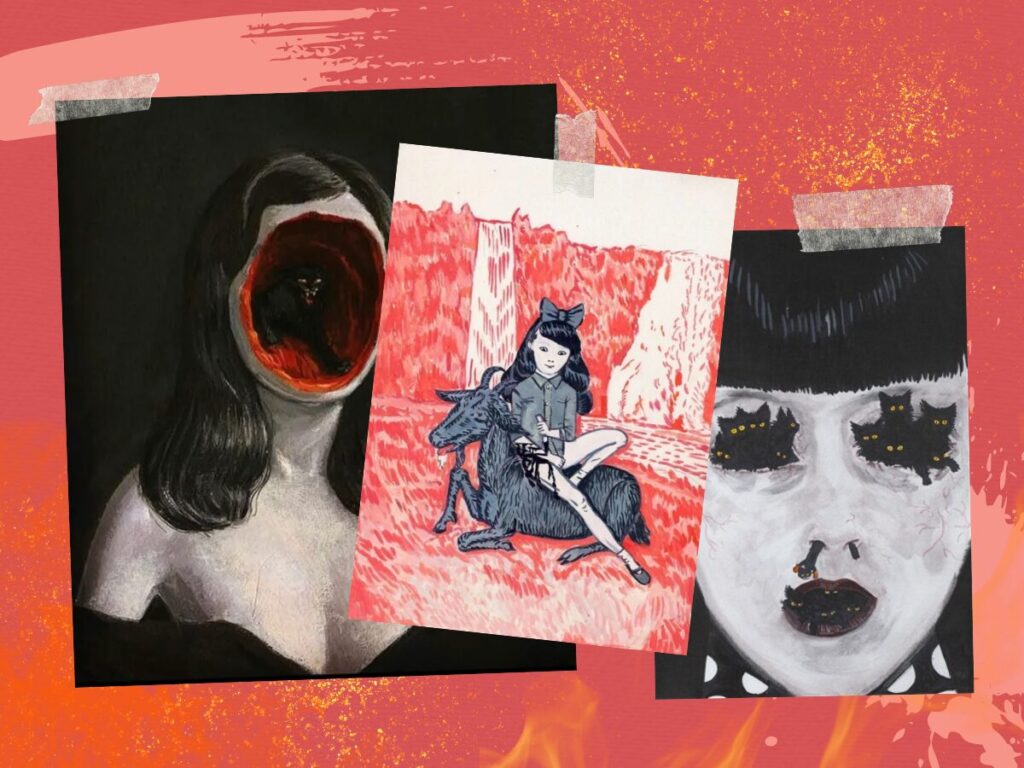

Her style is a fusion of mediaeval cacotopia and gothic romanticism. Drawing inspiration from Balto-Slavic folklore, particularly the vengeful spirits known as upiórs, Aleksandra populates her canvases with supernatural figures amidst modern urban landscapes. From seductive sirens to human animal hybrids, both beautiful and grotesque, and even hints of BDSM, all brought to life with gouache on canvas.

These morbid compositions borrow from the nightmarish visions of Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch and the cut throat social commentary of Francisco de Goya’s work. However, Aleksandra doesn’t simply replicate the past. She saturates her dark subject matter with a dystopian surrealism reminiscent of Polish artist Zdzisław Beksiński.

Her works often feature fatalistic female characters, acts of violence, and a sense of cynicism. Bloodshed, while present, is not the sole source of unease. Recurrent themes often feature the occult, death, and the taboo – allusions to cannibalism and paedophilia flicker at the edges of her work. However, it’s the psychological unease that truly grips the viewer. Aleksandra masterfully incorporates elements of the subconscious fears into her paintings. A recurring theme is the contrast of childlike innocence with acts of ferocity. Little girls, often depicted with an unnerving calmness, engage in disturbing activities that are at odds with their age. In ‘The Cuts’, a young girl is depicted sitting on top of a goat, seemingly unfazed as she carves into her own flesh.

It’s a twisted subversion of their expected innocence. These girls are not simply victims; they are complex figures who can both inflict and endure violence. “Death of a Paedophile” illustrates this duality, portraying a young girl standing triumphantly, urinating on the head of a fallen man. In contrast, some of the other works depict girls bound and vulnerable, at the receiving end of torture.

Aleksandra has openly acknowledged a fascination, since a young age, with depicting women bound and attacked by monstrous figures. This is a curious aspect of her works: a stated enjoyment in painting young girls in oppressive situations with the creation of perverse fairy tales where childhood innocence confronts sophisticated horrors. These narratives are often interwoven with a subtle eroticism, blurring the lines between vulnerability and power. One explanation for this fascination could be that it generates a feeling of terror that goes beyond graphic imagery by fixating on the violence itself and emphasising its aftermath or anticipation. This approach forces viewers to confront the uncomfortable reality of “evil” that may exist in the real world, a concept arguably more terrifying than any fictional monster.

Interestingly, she rarely captures male figures. If they do appear, they are relegated to bystanders or even perpetrators of violence. This could be her trying to reverse engineer the tired trope of the “evil feminine” and the objectifying male gaze that frowns upon the scorned, angry women.

As Rebecca Traister argues in her book “Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger,” women, especially those challenging the status quo, are often delegitimised through images portraying them as unattractive and shrill.

For men, anger is often expected and natural; however female anger is coded as ugliness, reflected in countless stories that relegate them to monstrous archetypes like harpies and witches.

This disconnection from the historical demonisation of female rage is prevalent in the 48-year- old artist’s radical vision.

Aleksandra breathes new life into classical themes by revisiting archetypal female figures. From the Christian Madonna and mediaeval maidens to pagan priestesses and mythical mermaids, she reimagines these characters through a distinctly macabre lens, placing female agency at the core of her visual narratives. There’s a clear corrective agenda at play on symbolist tropes. Her heroines are portrayed with individuality and full agency, devoid from moral judgement regardless of their actions. In contrast to the historical tradition of using generic women as allegorical representations of sin, temptation, or societal ills.

These women aren’t mere vessels for male anxieties; they’re carnally powerful figures who confront the viewer directly. They aren’t afraid of their desires, and their complex nature dismantles the expectations of women needing to repress their animosity in order to be appealing.

In past interviews, when pressed about the source of her paintings’ magnetism, Aleksandra brushes it aside, suggesting it might just be a fascination with sex and violence. There’s truth to that; however, there’s a captivating paradox at the heart of her art. Despite the artist herself prioritising form and emotion over instilling her work with overt symbolism, her morbid figures seem to yearn for interpretation.

Her unnamed paintings are open to interpretation, and some undeniably have deeper meanings beyond a display of the perverse. Certain works seem to grapple with motherhood, or rather the expectations of it. One chilling image depicts children hanging by chains in a cave, overseen by a monstrous woman whose body writhes with maggots that spread across the children’s corpses. Another features a reoccurring character, a mutant spider-woman with unconscious children trapped in her web. By placing a woman at the centre of this act of cruelty, Aleksandra forces viewers to confront the uncomfortable reality that evil can take many forms, and that the nurturing instinct often associated with traditional femininity or the expectations of a natural “maternal instinct” existing in all women, can be horrifically distorted and absurd. The painting may evoke feelings of fear, disgust, and confusion, prompting one to question the potential flaws in seemingly conventional roles.

Another way she disrupts the confined ideals of femininity is through her recurring use of cats, a symbol often associated with women, particularly ideas of purity and domesticity. These felines, often based on her beloved cat Mitusia, become protagonists who smoke cigarettes, or participate in violent battles and bloodcurdling rituals. They indifferently witness the tragedies and despair that unfold in her canvas.

Other paintings feature seemingly innocent cats marked with occult symbols. The juxtaposition of a cute, cuddly animal with a symbol associated with hidden knowledge or forbidden practices, can be interpreted as a metaphor for the historical persecution of women, particularly during the witch hunts. Throughout history, women who challenged societal expectations, who possessed knowledge deemed unconventional, or simply didn’t conform to the innocent, ditsy and submissive ideal, were often branded as witches. It was the very act of defying these expectations, this potential for female autonomy, that struck fear into the hearts of those in power.

But perhaps the most disturbing image is the depiction of cats literally emerging from a woman’s carved face. Possibly hinting at a violent rejection of societal expectations placed on women. The cat, often seen as independent and even rebellious, could symbolise a woman breaking free from the constraints of femininity, even if the process is messy and disturbing.

Aleksandra’s artistic influence extends beyond the canvas. She co-wrote the 2012 short film “The Capsule.” The film follows a group of women residing in a secluded mansion, overseen by a powerful matriarch. Their existence, seemingly bound by rituals that protect them from the outside world. This evokes the single-sex dystopias often depicted in her work, where women exist outside the constraints of a male-dominated world.

The lasting impact of Aleksandra’s work lies in its ability to provoke a counter-narrative, in a world that often seeks to suppress or sanitise female anger. By forcing viewers to confront the darkness within themselves and the world around them, she opens a space for a more nuanced understanding of femininity and the potential for agency that lies within the “Mad/Evil women” trope. Her own statement, “every time I paint I’m on the edge on saneness,” encapsulates this spirit.