It’s undeniable, Sabrina Carpenter has attracted quite the following. Whether it’s Kim Kardashian, Barry Keoghan or the Catholic Church, all eyes are on her. She’s no stranger to breaking boundaries; she’s hit No.1 on the Billboard Global Chart, supported Taylor Swift on her Eras tour, became the newest SKIMS girl and managed to get a priest fired. It’s been quite the year for this ex-Disney kid.

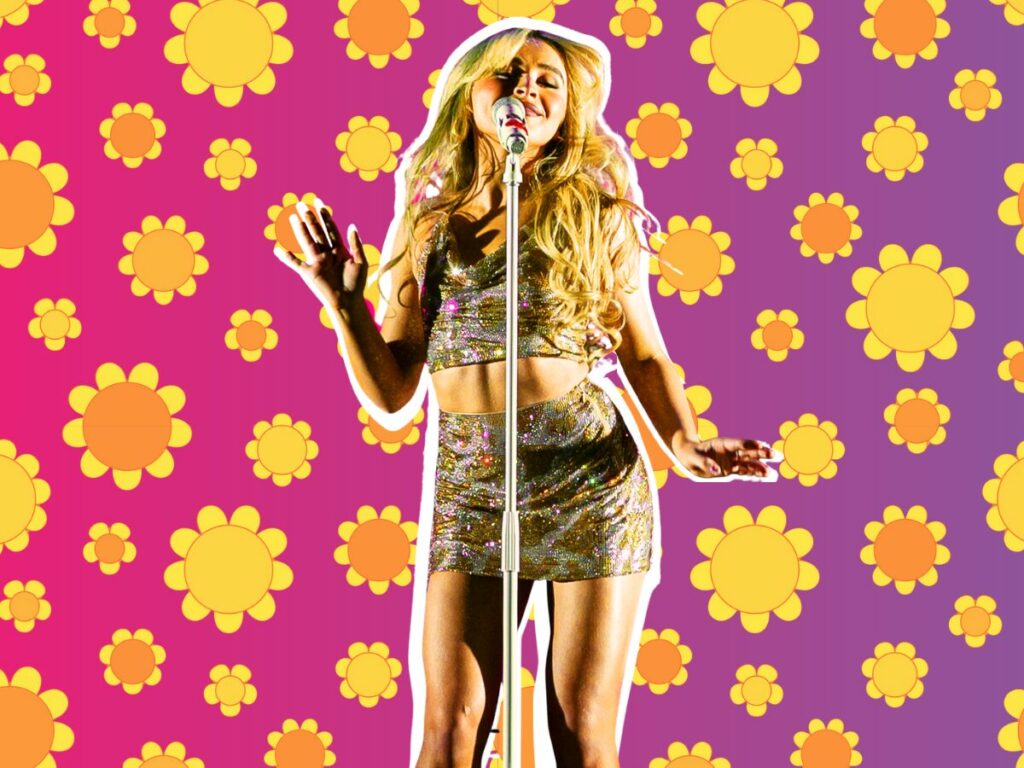

But, as she made her Coachella debut fitted in Robert Cavalli and a Brigette Bardot blonde blowout, it’s her hemline that has us talking. In keeping with this summer’s micro-skirt revival, she bounced on stage in quite possibly the cheekiest silhouette we’ve ever seen. Throughout her ‘Emails I can’t send’ tour, she’s curated this distinctive ‘Polly Pocket’ style. Doll makeup, retro 60s accessories and a hint of Y2K. She’s perfected the hyperfeminine coquette look. She’s in good company; as Barbie core lives on into 2024, Tyla, Bella Hadid and Cindy Kimberly have also been caught flaunting the micro skirt.

With her tongue-in-cheek lyricism, infamous Nonsense outros and flirty choreography, there’s something subversive and timeless about Sabrina commanding a stage in the belt-sized skirt. But what is it about a woman in a mini skirt that we find so rebellious?

The truth is, what we wear, especially for women, is never neutral. The mini skirt, more than most garments, has long been a site of politicisation and debates about freedom of sexuality, identity and expression. Hemlines had been rising in the post-war era, but it was Mary Quant and the “Chelsea Girls” in 1960s London who brought the mini to the mass market. Daring hemlines embodied the revolutionary spirit of the decade, with the legalisation of abortion and homosexuality, and the contraceptive pill becoming widely available. Young women were the fashion innovators of this new experimentative and subversive ‘youth quake’ cultural climate. In rejecting their mother’s wardrobes, they simultaneously rejected patriarchal expectations that generations of women before them had been subjected to. Bold, feminine and assertive; it is not surprising that this little silhouette stirred up some controversy…

Whilst some embraced the shifting image of femininity and all that it represented – it faced serious cultural backlash. Short skirts were condemned for being overtly ‘sexual’; American schools even banned skirts higher than the knee to prevent young girls ‘provoking’ or ‘distracting’ boys (sound familiar?!). At the time, China banned them completely and, even in 2013, Uganda reintroduced its ban from the 1970s. It’s clear, even into the 21st century, that instead of addressing why we are socialised to see women as sexual objects, societies (and governments) are still policing women’s appearances to fit a patriarchal moral code.

But the fundamental question is, why does women’s dress provoke such public comment at all? The reality is, although it might seem like we have progressed in terms of women’s legal rights, poisonous beauty standards still seep into the culture and media that we engage with every day. Whether you are attuned to it or not, cultural messaging painting women as passive sexual objects is hidden in plain sight. Take this headline from 2017. In the midst of Brexit negotiations, between two of the most influential politicians of the moment, Nicola Sturgeon and Theresa May. The Daily Mail had more to say about their skirts than their policies, and slapped on the front page for its 2.8 million readers the headline, “Never mind Brexit, who won Legs-it!”. The economy, our relations with Europe and our lives were in their hands, and media outlets were obsessing over Theresa’s ankles. Classic. It says all you need to know about how far we still have to go in our perception of women and their legitimacy as political players.

In feminist theory, we call this portrayal of the passive woman through a heteronormative lens for the pleasure of the imagined male viewer, the ‘male gaze’. First coined by Laura Mulvey in reference to women in film, it was later applied by John Berger to art history. A fun way to test this out – try walking around your city, count how many statues of women there are that are not naked or mythical figures. I guarantee it will be close to zero. Even when they unveiled a statue in London of Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the most influential feminist thinkers of all time, they chose to portray her as a tiny naked body.

Whether it’s shoes, clothes or cigs, the commodification of women’s bodies for profit is ubiquitous. ‘Male gaze’ advertising is everywhere. Some of the most notoriously misogynistic campaigns came from American Apparel; their 2013 ‘Back to School’ advert featured young girls, practically naked, from voyeuristic angles. “So what? It’s just an advert?”; I’ve heard this, countless times. Public sexualisation of the female body from a voyeuristic, and frankly paedophilic, perspective is exactly how the normalisation of gendered violence starts. It’s not surprising that founder, Dov Charney, got fired from his own company for numerous sexual assault allegations. Eventually, the ‘Back to School’ advert was banned and American Apparel went bankrupt, but the story is far from over. Charney, now 55-year-old and CEO of Yeezy, still thinks (bear in mind most of his models are barely adults) that “Sleeping with people you work with is unavoidable”.

So, we’ve established that this was never really just about the skirt. It’s about how patriarchy still permeates media and culture, and how this shapes how we look at women’s bodies and clothes (especially the mini skirt). It’s one of the most subtle ways we police other women, and ourselves, through a patriarchal gaze. As John Berger said,

Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.

What does this all mean for Sabrina? In the context of the last year when the girls have been reclaiming hyper-feminine looks, for no one else but themselves, her mini-skirts are one big middle finger to the patriarchy. After escaping a five-album contract with Disney – who had a say in her art, finances and wardrobe – it’s the perfect outfit to accompany Emails I can’t send. Honest, flirty and vulnerable at times, this is Sabrina, authentically taking control, as an artist and a woman.

Existing is political. In an era of heightened media scrutiny, how we move, express and even dress ourselves invites public commentary. We’ve all been socialised to treat women’s bodies as public property. So, if you ever have that nagging sense of self-policing body shame we’ve been taught to feel since we were little girls, just imagine Sabrina, in her belt-sized skirt, singing “my give a fucks are on vacation”.