Synonymous with its 4/4 beat, dance tempos, and disco/soul influences, house music changed the music scene forever and continues to evolve, with numerous genres growing from the movement that started back in Chicago. House music was born from protest and the need for a safe space. It is a genre whose origins are rooted in Black and LGBTQ+ history and continues to bring people together worldwide today. In fact, it is the most popular genre of music in the UK, according to a study by A2D2.

The origins are often overlooked, and many people still question what house music really is. Many songs falling under the genre tend to be genre-bending and span a wide range of sub-genres, but at its core, house music is protest music. Warehouse was opened in 1977 in Chicago by none other than Frankie Knuckles. He was the father of house music, and a few years later, his influence spread around the globe. The club began as a members-only club, mainly frequented by Black and Latino gay men, and was seen as a place for members of the LGBTQ+ community to party safely. Minorities throughout history have rarely had safe places to exist; in the birthplace of ‘house’ itself, homosexuality was classed as a mental disorder, and across the USA, homosexuality was illegal and fundamental rights were denied to people who were suspected of being gay.

Four doors down in New York City, gay bars were also pushed underground and subject to constant police raids. We all know the most famous of these bars to be Stonewall, where Marsha P. Johnson allegedly threw a brick at the police and the world was forever changed for LGBTQ+ people globally. Patrons and onlookers fought back against the police at Stonewall in 1969 for days, fighting for their bar and their right to exist and fighting for all other gay establishments throughout New York City that served as spaces to have fun without the fear of discrimination.

It wasn’t until the ’80s that Frankie Knuckles introduced the world to ‘house’ due to the literal death of disco and having to make soul music ‘danceable’. I say the literal death of disco music because that is what it was. Disco records were destroyed in a racist protest nicknamed ‘Disco Demolition Night’ where a trailer of disco records was blown up, and participants could gain reduced entry to the White Sox game if they brought a disco record to be destroyed. This was because Steve Dahl, a musician and radio host, was fired from WDAI and, in retaliation, promoted the White Sox game by offering reduced admission if entrants brought a disco record to destroy. However, some people thought disco records meant any record by a black artist. Thousands of records were destroyed in one night, and it was seen as a landmark event for the death of disco music. Coinciding with this event, police officials across the USA, but especially in New York, began raiding disco nightclubs and destroying anything of value.

In Warehouse, Frankie Knuckles would use old disco records, a reel-to-reel tape deck, and turntables to splice/re-edit records on the spot. This caught on, and other DJs found inspiration in Knuckles. House music grew, and when Knuckles left Warehouse to form Power Plant, House had infected all corners of the globe and had already established a name for itself. In house, disco found a place to quietly continue existing and unite people.

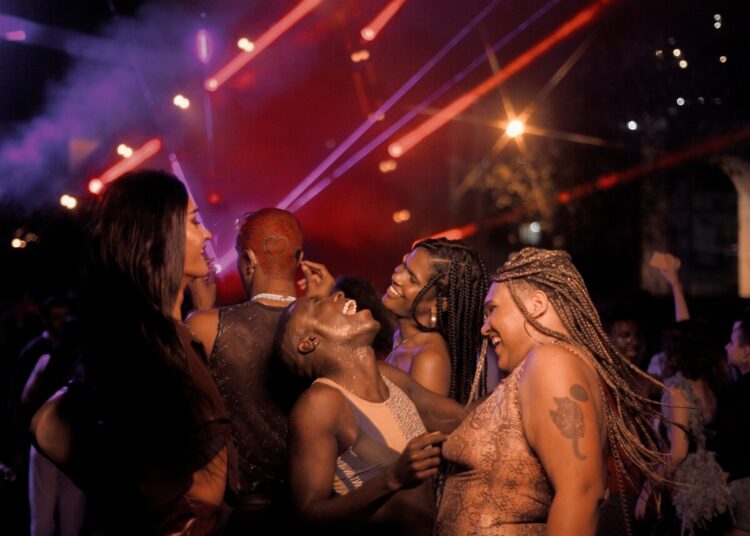

Personally, my first introduction to house music was your typical British teenager experience, off someone’s iPod at a house party with cans of Frosty Jack and Strongbow scattered around. Or, it may have been in a field. Or, it may have even been when I snuck into Powerhouse, a gay club in Newcastle, underage. Clearly, I do not remember my first introduction; however, I do know that the parties I would frequent as a teen and the clubs I frequented in Dundee as a student were some of the first and only places I felt comfortable being authentically myself. It is quite fitting that the first person I came out to as bisexual was also a DJ. Music helped me find the friends I consider family and helped me express myself authentically. Reflecting on this experience, I often feel humbled because I know this feeling of belonging is often rare and is sought for. The sense of safety and belonging is also why ‘houses’ were made and why ballroom culture, where house music is played, is so important.

Ballroom culture tends to be forgotten when house music is being discussed, but I do not think you can talk about one without talking about the other. Ballroom culture grew from the need for a safe space for Black and Latino LGBTQ+ members to express themselves and dance, wear drag, and perform for their peers. The influence of ballroom culture still runs deep today, from music to fashion to film. ‘Houses’ were literally houses within the ballroom community that functioned as alternative families and where shelter was given to mostly Black and Latino LGBTQ+ members. These houses are led by ‘mothers’ and ‘fathers’ who are experienced ballroom culture members; the other members are their ‘children’. All of the ‘children’ are each other’s siblings.

Other than dancing, music is a massive part of ballroom culture; the ball does not exist if the music is not there. If you go on Spotify and select a ballroom playlist randomly, you will be met with music that elevates queerness, feminity, and a range of genres. Historically, the music would be whatever was currently prevalent within the Black LGBTQ+ scene, which led to house music being one of the prime sounds emanating from these ‘ballrooms’. Today, house music is the primary sound of ‘balls’, many old classics are remixed, and ballrooms are still considered fertile ground for developing new house music and other sub-genres.

House music continues to significantly impact society today, extending beyond its origins to influence various aspects of society. It continues to be a genre that unites people from different backgrounds and still provides a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community to enjoy themselves. The evolution of house music as an archival institution rooted in the history of disco continues today, and so does the essence of protest. DJs such as Honey Dijon defend the authentic spirit of house music, and house music continues to inject every corner of the world. More recently, “HOUSE AGAINST HATE”, took place outside the UK Prime Minister’s base at 10 Downing Street, which called on the United Kingdom to stop hate against minority groups while simultaneously raising funds for Medical Aid For Palestinians.

As Pride Month continues and Pride marches happen around the world, it is important to remember how much LGBTQ+ individuals and communities have done for culture and music. House music provided safe spaces for these communities, and in turn, LGBTQ+ culture helped boost the popularity of house music, making the genre into the giant it is today.