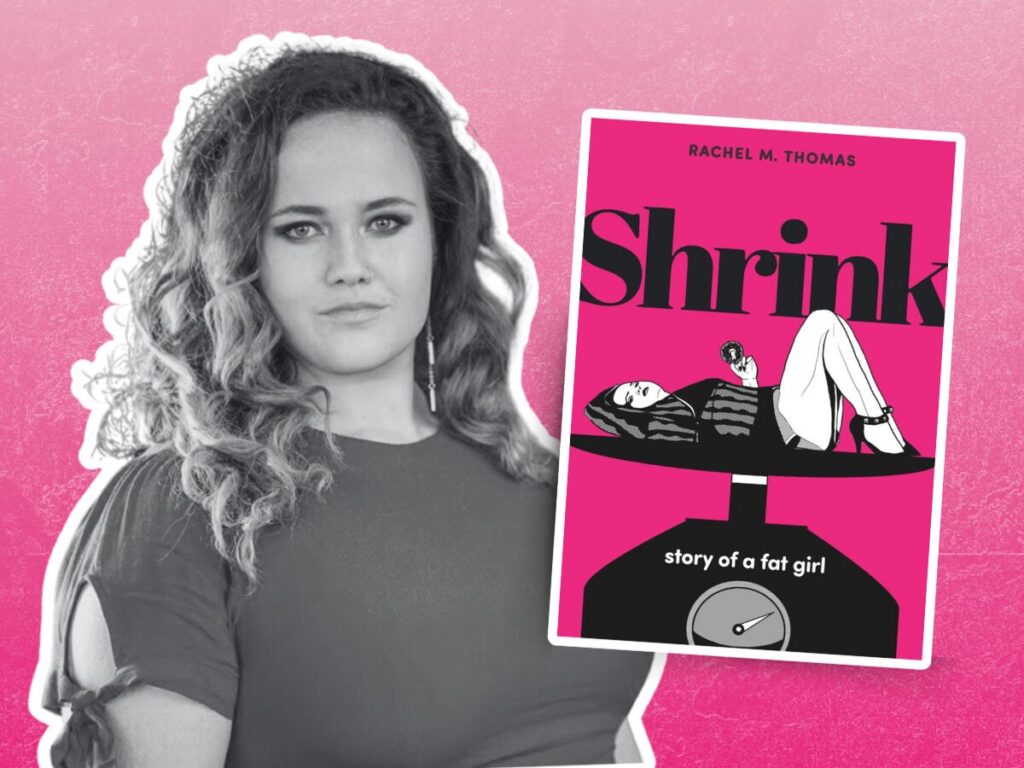

What inspired Shrink?

“I spent my entire life living in a fat body, and I was going through the experience of losing weight, and wanted to understand that better from a medical and sociological viewpoint, which also coincided with the work I was doing on my PhD.

“ When I was working on my PhD, I was working in three disciplines: medical sociology, medical history and fine arts. At the time, I was working on a medical sociological study that was looking at the experiences of women living in fat bodies and their experiences with IVF in the medical community. We were putting this article together and it occurred to me that the people who would benefit the most from this information may not be able to access it simply because of how we were writing the paper (the jargon used and potential paywalls). If you want to read a journal article and aren’t affiliated with a university, you have to pay. I was trying to figure out a way that I could take all of this really important information about the obesity epidemic, around fat shaming and put it into a format that was accessible. So with my fine arts background, I decided that the graphic novel would be the best approach, and so that’s how Shrink came to be.”

“It’s a seamless blend between a ton of research and the translation of complex, sometimes very complicated medical and sociological research into a form that’s accessible, which is informed by my personal experiences.”

What is graphic medicine and how does it apply to this graphic novel?

“Graphic medicine is an interdisciplinary discipline that sits at the intersection between comics and healthcare. So again, it’s about making things accessible for patients, but it’s also about explaining difficult experiences to doctors as a means to improve patient interactions

“In the context of Shrink, obviously, we know that there’s a lot of fat shame within the community, especially coming from healthcare professionals. And so having a graphic novel that really describes the experiences of living in a fat body in social and medical contexts is important, not only for people who are also living in a fat body, but also for doctors who want to know more about patient experiences and to address their own biases when it comes to fat bodies. It’s a fairly new discipline. It was officially coined in 2008 by a British medical physician, Dr Ian Williams, but it’s been growing in terms of scholarship and readership in the past few years.”

Why did you choose a graphic novel to speak on the medical and social implications of living in a fat body?

“Fat bodies are underrepresented in comics, and when they are represented, it’s in very stereotypical ways. You don’t necessarily see fat heroes. You’ll see idealized bodies, the Femme Fatale, overly feminized, hyper-sexualized bodies, but you very rarely see a fat body in the place of a hero. Shrink is a testament to making a fat body a hero.

“Thankfully ideas are shifting in terms of what makes a body illustration worthy. I used a traditional approach in terms of the actual drawing style itself, but in place of the idealized hero, you’re using a fat body instead. It’s meant to trouble the ideas around who is allowed to be illustrated.”

What do you want readers to take away from the experience?

“Ultimately, Shrink is about this idea around choices. We get constant noise as fat bodies about, our moral obligation to lose weight, but then it’s also seemingly a bit impossible. Finding workout clothing, for instance; being fat-shamed at a gym; and doctors not able to provide useful information. It’s always boiled down to “just lose weight and exercise. There’s never a detailed approach to doing that. They never consider social determinants of health, like your gender, your economic status etc.: all of the things actually contribute to what actually causes the body to be “fat”.

“Ultimately, it’s reviewing all of these things, as well as the other side, the body positivity movement, or a fat acceptance movement, considering all of these things, and informing the reader that they do have a choice in all of this. The story ends on a question mark: does the hero actually end up gaining the weight back after fearing it for so long, was she one of the few who was “successful” in taming her body? Fundamentally Shrink encourages the reader to consider their own body and story, to choose whether or not they want to lose weight in social and medical contexts that are completely contradictory to each other. Ultimately, it’s about choices. Do you lose weight or do you not lose weight in this constant contradiction?”

What are the core ways that the links between fat bodies and health are misrepresented?

“Fundamentally I think the body mass index plays a role in the misrepresentation. In the 90s we had the international obesity task force (IOTF) that was lobbied the World Health Organization (WHO) to change the scale in terms of what the cut-offs were for overweight and obesity. But, what happened overnight is that a huge proportion of the population became either overweight or obese without eating anything.

“Unfortunately, teaching BMI is common in t medical schools and is still seen as being an accurate indicator of determining your overall health what comorbidities might occur and mortality rates. We know that the experience of fatness is a far more nuanced thing than that, it doesn’t always come down to your height, or your weight. We even have studies that have examined the idea that your survival rate as you get older increases if you have a little bit of extra weight around your body.

“Unfortunately, the BMI scale is used to threaten fat bodies into submission rather than more accurate predictors of illness, like waist circumference. It also doesn’t take into account any social determinants of health, such as what are people eating? Do they have access to nutritious food? Are they able to afford nutritious food? If you’re a single mother working three jobs to raise your kids, when do you have time to do the recommended 150 minutes of exercise per week? These nuanced ideas that don’t involve BMI are rarely taken into account.

How are fat bodies constructed in relation to morality?

“There is an association with fat bodies being deviant in some way, and the expectation is that you should change which is constructed through institutions like medicine.

“There’s also what I like to call performative morality. This is where you have fat bodies that will only go through a weight loss process to perform as a more normal body. And that’s everything from, you know, social media posts about weight loss, exercising and posting about what you’re eating to prove you’re addressing your morally offensive body. Fat bodies are expected to be constantly involved in this sort of performative morality. They have to prove they are changing their bodies because they don’t fit in medicine or society.

“And so I think that’s a really interesting point that people may take away from Shrink as well. As you know, at what point do we stop being performative with this? At what point do we realize that being fat is not a moral problem, you can’t morally blame someone for being fat, because it oftentimes has nothing to do with the individual and everything to do with the circumstances, genetics, gender, environment?”

In what ways is Shrink different to the traditional weight loss narrative?

“It is a story about going through the process of weight loss, but it never shows these markers of health that we commonly associate with weight loss. It never shows weight on the scale. It only vaguely indicates to the reader what might have happened. It’s taking away one potential trigger for people, which is the idea of finding a specific weight on a scale, which we know isn’t indicative of health or morality.

“The other different thing is that in the end, the main character has this revelation that ‘I’m actually making myself sick going through this process.’ It’s created disordered eating. It’s created an unhealthy obsession with exercise, tracking calories, with tracking food intake, to the point where she gets idiopathic hypertension because of the process of losing weight. Gaining some of the weight back was the healthiest thing that she could do. Fundamentally it takes away this idea that losing weight and becoming skinny, is the be-all and the end-all. But again, the ending is open ended and so what works for the hero doesn’t necessarily work for the reader and I think that’s the key message. It’s about choice, it’s about making informed decisions about your own health and autonomy. We don’t know what happens to the hero after the book, and it’s not necessary. Shrink is meant to help readers get a start at analysing where their bodies might fit in this debate.

“There are very few English language graphic novels on this subject and none that quite do what Shrink has done. There is The Big Skinny, by Carol Lay, which unfortunately is the exact opposite of that. She is the quintessential bio citizen. She is doing all of the performative morality checks as a fat body correctly. She’s losing weight, she’s tracking her calories, and then she will end up fitting into this perfect dress at the end. And I don’t think that’s a ly healthy way to present this information, because it’s only exacerbating an issue that we already see happening: that losing weight is the only path for a fat person to take, that you have to lose weight in order to be of value in society.”

How can people address their internalised fatphobia?

“I think that just realizing that it’s an actual issue is the first step to catching yourself in these moments because we all have them. It’s ingrained in us from an early age that fatness is bad, and that you never want to be fat. I grew up in the 90s and internal fatphobia was taught to all of us so it’s hard to get out of that loop. Having pieces like Shrink might help us start to recognize these thoughts as a first step in addressing that internalized fatphobia. I like approaching it as if my first impression of a person is usually what society has dictated, but my second thought is usually closer to what you actually think. You’re absolutely going to have certain thoughts because of how we’re conditioned by medicine and social norms, but making sure that you do have that second impression is what is going to start to make a meaningful change.