Gaeilge means Irish; both refer to the ‘Irish language’ and they are used interchangeably throughout this article.

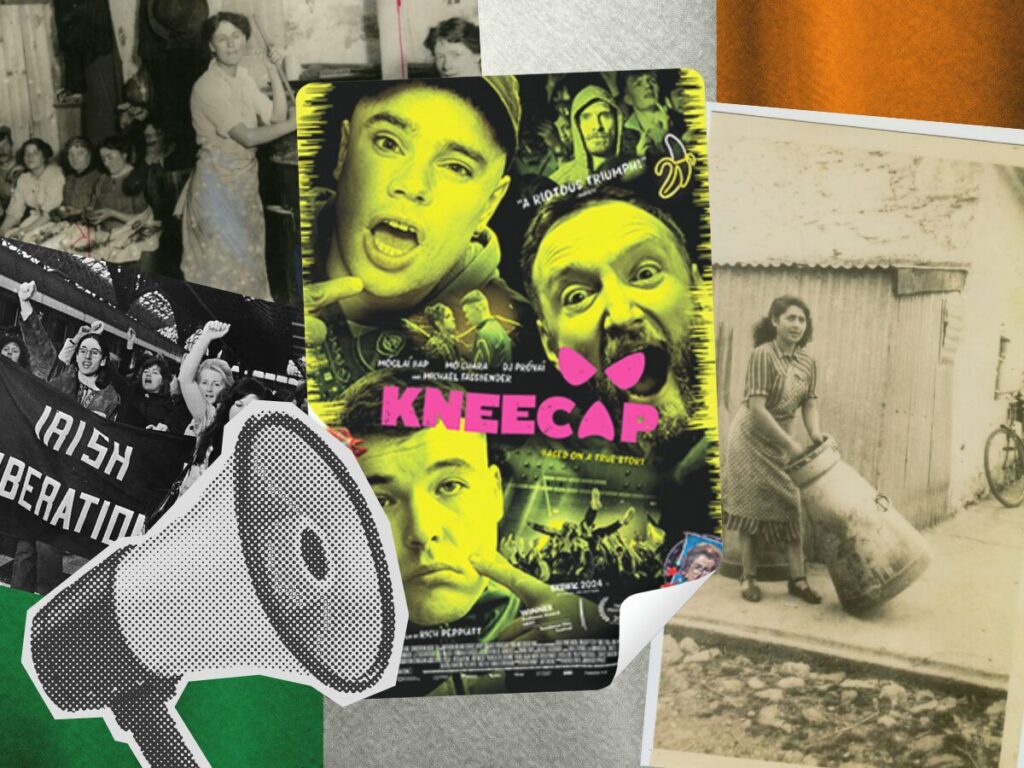

Walking out of the cinema and immediately opening Letterboxd to give a 5* rating to a film entirely in Gaeilge had not been on my 2024 bingo card. What had started as a fun trip ended in a crushing feeling of disappointment in myself—my Grandad was Irish. Yet, I don’t know a single word other than ‘sláinte’ when I lift my pint and ‘Fenian’ when I talk about my families history. I believe shame can be a powerful form of oppression, so instead I deep-dived into everything I could to boost my knowledge of languages that had died somewhere in my bloodline. The majority of my family is at least bilingual; my other Grandparents could speak five languages, and somehow all these languages stopped at me—an English girl. But, through all the stories I learnt, one thing that stuck with me was how feminism, women, and the protection of Gaeigle are deeply intertwined.

Kneecap (2024), the movie lightly touches upon the role women play in the Irish language movement. Although the main focus of the movie is the musical trio, actress Fionnula Flaherty’s character is just as important. Caitlin, played by Flaherty, embodies the spirit of language activism and reflects the real-life contributions of women who tirelessly advocate for the language through teaching, organising events, or creating spaces where Gaeilge can continue to thrive. She embodies the spirit of language activism in such a subtle yet important way that it echoes the real-life stories of countless women who have championed Gaeilge, ensuring its survival.

Flaherty’s portrayal of Caitlin underscores the resilience of women who work to make Gaeilge accessible to the next generation. By engaging with communities, hosting events, or advocating for greater support for Irish-medium education, these activists build the infrastructure that allows the language to thrive. Caitlin’s role also connects to the broader historical narrative of women as language activists. During the colonial suppression of Gaeilge, women played a crucial role in keeping it alive within the home, passing it down to their children even when it was pushed to the margins of public life. In the North during the Troubles, women were instrumental in underground language movements, teaching Gaeilge informally and fostering cultural pride as an act of resistance.

Colonialism has a devastating impact on language. To a large extent, colonial views are internalised through generations, and the British rule really made sure of this. Gaeilge became linked to the idea of poverty, exile and death, as stated by late poet Seamus Deane in his analysis of records from the Great Famine. Even the ‘Emancipator’, Daniel O’Connell, advocated for discarding Irish in favour of English as he saw it as a tool for advancing the rights of Irish Catholics. Gaeilge was then largely abandoned after the famine and with the systematic oppression of the language, the number of speakers steadily declined.

The education system was a prime way to suppress the language. For instance, the use of the “bata scóir” (tally stick) punished children for speaking Irish, marking a stick each time a student was caught using the language, with accumulated marks leading to physical punishment. This suppression has been successful in part, with Gaeilge now being one of the 12 EU languages at most risk of extinction. However, in response to such oppressive measures, Irish families, and notably women, became the custodians of the language within the home. While specific documented evidence highlighting women’s roles in this context is limited, it is widely acknowledged that women, as primary carers and central figures in family life, played a crucial part in transmitting Gaeilge to their children. By continuing to speak Gaeilge at home, mothers and grandmothers ensured that the language persisted through generations.

Their efforts laid the foundation for later revival movements, which sought to reclaim and promote Irish heritage and identity. Women’s roles in movements like Cumann na mBan and the broader republican struggle often intersected with their commitment to Gaeilge. Teaching the language in secret or using it to communicate within tight-knit communities was a form of resistance. Daisy Carson, a Gaeilge advocate on TikTok, reflects on this connection, saying, “Activism for the language brings women from all over the island together for one strong-willed purpose: to learn, speak, and keep their language alive.” Today, online communities have become a lifeline for connection and resources. For Daisy, this accessibility is deeply personal. Living in the North, she struggled to find nearby programs or in-person classes. She states, “The online community has been so supportive and has provided me with really useful online resources” which shows activism in the form of music, social media, and film is incredibly important.

As Gráinne Aoibhinn, an Irish content creator and language advocate, reflects, “Gaeilge is my first language, and I was immersed in a culture that spoilt me with plenty of female role models.”. She highlights how old Irish legends often depict strong women, from Gráinne Mhaol shaving her head to escape marriage and Bríd removing her eye to avoid a similar fate. These stories do not just celebrate rebellion; they normalise female agency. In the age of social media, women are taking Gaeilge to platforms where traditional gatekeepers don’t exist. “The Irish language gives women a voice,” says Gráinne, pointing to the number of Irish-language podcasts and social media channels run predominantly by women. Daisy explains how online communities have revolutionised language learning: “Social media makes the idea of learning Irish (and the practicality of it) more manageable. It has also greatly improved the accessibility of the language.”

Irish-language music has also played a crucial role in bringing Gaeilge to new audiences. Daisy calls music “one of the most influential parts of the language’s persistence.” Groups like Kneecap have made Gaeilge accessible and modern, while traditional and folk artists such as Amble and Ye Vagabonds keep older forms alive. Like Irish filmmakers, these artists bridge the gap between the old and the new, making Gaeilge relevant to contemporary audiences. The Kneecap movie is just one example of how Irish-language media is gaining global traction. Films such as Small Things Like These and Disney+ projects about the Troubles are helping international audiences understand Irish history and culture through authentic storytelling. “The thing I find most influential about Irish artists is that very few fail to be activists,” Daisy says. Whether through language, politics, or human rights, Irish creators continue to carry forward a legacy of resistance and hope.

The intersection of feminism and the Irish language continues to play a vital role in the growth and resilience of Gaeilge. Women today are not only preserving the language as a cultural cornerstone but also using it to challenge societal norms and amplify their voices. Social media has emerged as a powerful platform for this activism, enabling women like Gráinne Aoibhinn to make Gaeilge accessible and relevant to modern audiences. Daisy Carson underscores the importance of these digital platforms, explaining, “Social media makes the idea of learning Irish (and the practicality of it) more manageable.” For many women, platforms like Instagram and TikTok offer new opportunities to reclaim their heritage and connect with others in ways that traditional institutions often cannot provide. “It’s about creating a sense of community and support,” Daisy adds, “especially for those of us in the North who don’t have easy access to the Gaeltacht.”

The survival of Gaeilge through centuries of colonialism is a testament to the resilience and dedication of women who refused to let their language be killed. Through powerful acts of resistance, women ensured that Irish culture and identity endured, even in the face of systemic oppression. Their legacy lives on today in the continued growth of the Irish language and the slow but steadily increasing number of Irish speakers. Gráinne highlights the importance of Gaeilge for shaping the younger generation, explaining, “The stories we are told as children have a strong impact on how we view the world as adults. I think we could be raising a lot more feminists by reading old Irish legends at bedtime.” Stories of figures like Gráinne Mhaol and Bríd not only help preserve the language but also instil values of strength, independence, and resilience in future generations. Today, women remain central to the Irish language movement as educators, activists, and storytellers, continuing the legacy of those who came before them.

As Daisy aptly states, “A passion for the revival of Gaeilge means a passion for the right to freely and safely express and take pride in your own culture.” By keeping this passion alive, women have not only shaped Ireland’s past but are actively defining its future. Finally, ‘revival’ may not be the best word for this resistance; revival would indicate that Gaeilge has died and been brought back from the dead, but as we have learnt, it never really died and has survived under the cracks of colonialism thanks to the strong women in Ireland.