Content warning: This article contains mentions of domestic violence.

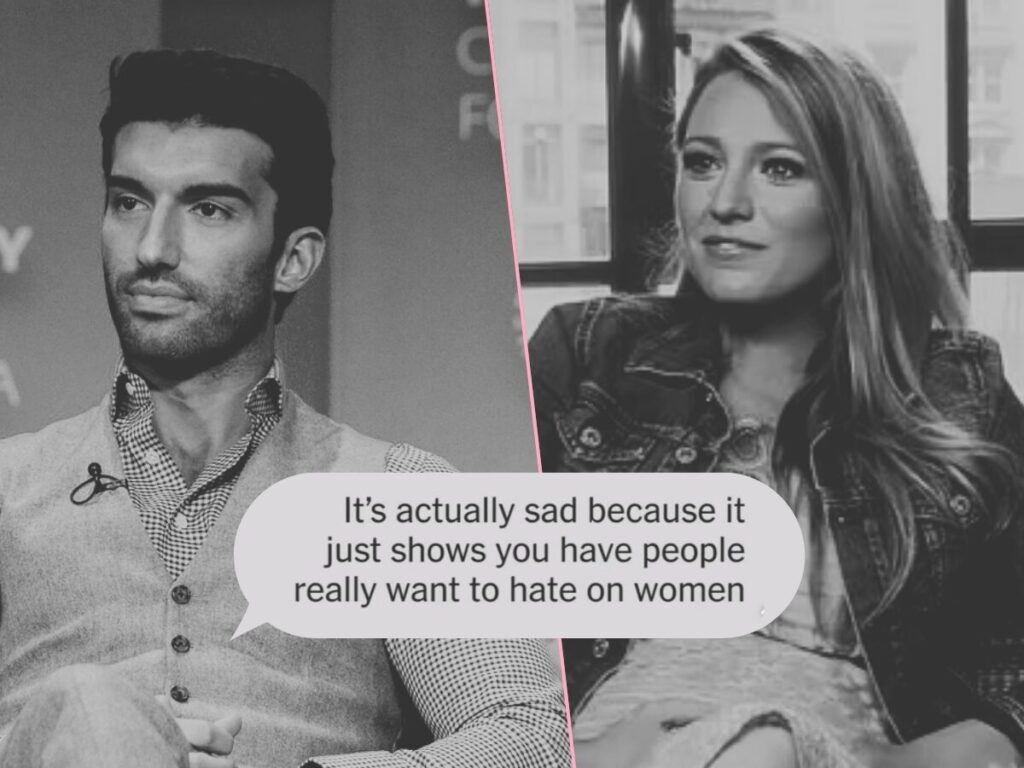

In 2024, Blake Lively became the face of an uncomfortable truth: Hollywood can’t talk about domestic violence without dressing it up as something pink, sparkly and romantic. She egged audiences on to see her film It Ends With Us (2024) on girls-night, decked out in flowers – after asking them to try out her new hair-care line. I directed my anger towards such insulting marketing at Lively. Then she filed a complaint against Justin Baldoni, her co-lead, director, and co-owner of the film’s production company, Wayfarer Studios. Things changed.

The complaint, released by The New York Times in December alongside an article, alleges that Baldoni sexually harassed and set up a smear campaign against Lively. According to the document, he and others created a “hostile work environment”, particularly for women. Once promotional efforts began, Lively alleges, Baldoni “created, planted, amplified, and boosted content designed to eviscerate Ms. Lively’s credibility”.

A plethora of claims detail Baldoni’s on-set behaviours. Some are downright odd: apparently he “claimed he could speak to the dead”, particularly Lively’s late father.

Others, if true, are plain to see examples of sexual objectification. He “often referred to women in the workplace as “sexy”’. He reportedly “pressured Ms. Lively (who was in her pre-approved wardrobe) to remove her coat’ before saying “I think you look sexy”’. When Lively had strep throat, he apparently gifted her the contact details of a medical professional who turned out to be a “weight-loss specialist”.

One unnerving claim even involves Baldoni admitting to possible sexual assault in “a car ride’’ by saying “Did I always ask for consent? No. Did I always listen when they said no? No.”

I’d been naïve – quick to blame a woman who may be a victim, not just a power-hungry star battling for creative control, single-handedly wrecking an essential message about domestic violence. Even more naively, I assumed that the thousands commenting on Lively’s Instagram posts shared my embarrassment. But they were sharpening their pitchforks.

Under her December 12th Instagram post, the only one for months with unlimited comments, sit tens of thousands of vicious snipes at her personality, appearance, and humanity. Some have up to 5,000 likes. Many of them appear to be written by women.

One user says, “History tells it all… She manipulates the truth and has a bad history of ego and power”. Another points out “You made this man’s life miserable” and “The entitlement of it all.” A comment that simply reads “Mean girl” has 1,147 likes.

Concerningly, a commenter suggests that even if the claims were true, they’d still support Baldoni because Lively “Forced him to be in the BASEMENT!!! On his Big Night!”. “Even if he did [the] smear campaign, I’m with him.”

This probably refers to a circulating alleged voice note in which Baldoni says he was ‘sent to the basement’ at the film’s premiere.

X is equally flooded with the view that the complaint is a ploy: one user admits “I don’t believe any of this” and that Baldoni “check[mated] her into showing us her true colours”.

User @DaveOsuna claims that it’s “been known in LA for years that she is toxic on sets”, so “this is a PR nightmare, and her team is doing everything they can to save her reputation”.

Granted, Lively isn’t exactly the poster child for good celebrity behaviour. In the thick of the onslaught, journalist Kjersti Flaa posted her awkward interview to YouTube, amassing over six million views and piles of comments calling out Lively’s rudeness. Tabloids are still digging up clips of actors mentioning Lively to spawn theories she’s challenging to work with.

But even if that’s true (and it may be the work of said smear campaign), why does that mean we don’t believe her when she says she was sexually harassed and conspired against? Why does being unlikeable mean you can’t be a victim?

In her Guardian piece, Arwa Mahdawi suggests that this ‘increasingly nasty legal battle seems depressingly like a rerun of the misogynistic hell that was the Johnny Depp v Amber Heard trial in 2022.’ Mahdawi’s right – this isn’t the first time a perceivably unlikeable female celebrity has been condemned online for ruining a man’s life. I’m pretty certain that, on social media, Heard will forever be called every name under the sun while Johnny Depp gets a halo and a hashtag. Meghan Markle is another example – she alone got the whole nine yards of misogynistic and racist online attacks for a joint decision to step away from royalty. What we’re seeing with Lively has been seen before.

The things she has alleged are also recognisable. I’d sat through that kind of uncomfortable car journey and endured a conversation like she allegedly had. I’d been called sexy walking home in my school uniform. But when Blake Lively claims she was called sexy in her work uniform, doing her job, the internet thinks she’s digging her grave?

Maybe the online backlash shows that the dangerous norms painting women as liars, co-conspirators, supernaturally evil, and worse for centuries have been repackaged, given a new lease of life in apps, usernames and comments sections. In the platforms that champion self-expression, women are the exception to the rule.

And in the very powerful, very skewed court of social media, where everyone has far less information grounding their judgement and far more freedom to judge anyway, the verdict nearly every time finds women guilty and men innocent. Unfortunately, these platforms are modern breeding grounds of misogyny and one historical prejudice: women can’t be victims if they’re not perfect.

It’s also unnerving that while Lively’s been pretty much radio silent about the situation until now, Baldoni spent much of 2024 reflecting on gender roles in his podcast Man Enough and quoting Bell Hooks. He won (and has now lost) an award in December for showing courage and compassion when advocating on behalf of women and young girls. Do these make Baldoni a feminist? Or are these, as Lively claims, tactics to polish his ‘ally’ reputation while he ruins his victims, ensuring that if she spoke up no one would be convinced? I don’t know. Given his choice of lawyer for a $250 million libel lawsuit against the New York Times, it’s certainly possible; Bryan Freedman is said by The Hollywood Reporter to have previously settled a case accusing him of sexual assault while at University.

Outside of comment sections, the situation’s not-so-level playing field is thankfully being noticed. In an IndieWire article, lawyer Nicole Page notes ‘that the alleged behaviour of Baldoni and Wayfarer comes straight out of the “Sexual Harassers Guide for Dummies” playbook: if you sexually harass a woman and the woman complains, a) deny, deny, deny; b) try to silence her through payoff or intimidation;’ and c), ‘conduct character assassination.’

Page also acknowledges that ‘Women who are brave enough to speak up are taking an enormous risk, yet the “she had it coming” backlash is quick and relentless.’

‘No matter how often we are reminded that with social media, manipulation is the feature not the bug, we fall for stereotypical tropes about women again and again.’

So, I don’t know what happened on the set of It Ends With Us. We won’t know for a long time, or maybe we never will. Regardless, a detailed, serious testimony is being seen online as the smoking gun in an investigation against women – and not as a terrifying reality check. Though the truth of the matter is uncertain, one thing is all too clear: if a woman defends herself and shares her sufferings, people are ready to attack. Social media is simply the new stage for this to play out.

In the UK, call Galop’s National Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans+ Domestic Abuse Helpline on 0800 999 5428, the national domestic abuse helpline on 0808 2000 247 or visit Women’s Aid. In the US, the domestic violence hotline is 1-800-799-SAFE (7233). Other international helplines can be found via www.befrienders.org.