A troubling pattern of physical aggression is emerging on UK streets, where women are being slammed, shoved or knocked aside without warning. In Japan, it’s called butsukari. And now, it’s here.

A woman walking. A man barging. No confrontation. No apology. Just a blunt impact that forces her out of his way. It’s ritualised dominance masquerading as random contact, and although it feels new, it has a name with ancient roots: Butsukari.

What is Butsukari?

Butsukari-geiko originated as a sumo training exercise in Japan. One wrestler rams themself into another repeatedly, pushing their opponent back across the ring with pure physical force. It’s an assertion of dominance; one body overtaking another, again and again. Within the confines of a traditional dohyō (sumo ring), the act of butsukari is mutual, disciplined, and ritualised.

In recent years, Japanese women have reported experiencing something eerily similar in a range of public spaces.

Sandyinjapannn, a Japanese content creator, first brought visibility to this phenomenon in 2024, compiling stories and theories. “They usually aim for women who they think look weaker than them,” she explained. This observation followed a video she posted outlining four theorised motivations for butsukari outside the ring, all centred around some form of dominance. Dr Ayako Kano, a gender studies scholar specialising in Japanese martial traditions, echoes Sandy’s insight: “Butsukari is about force meeting resistance. But outside the ring, when one party isn’t consenting to contact, it becomes about control.”

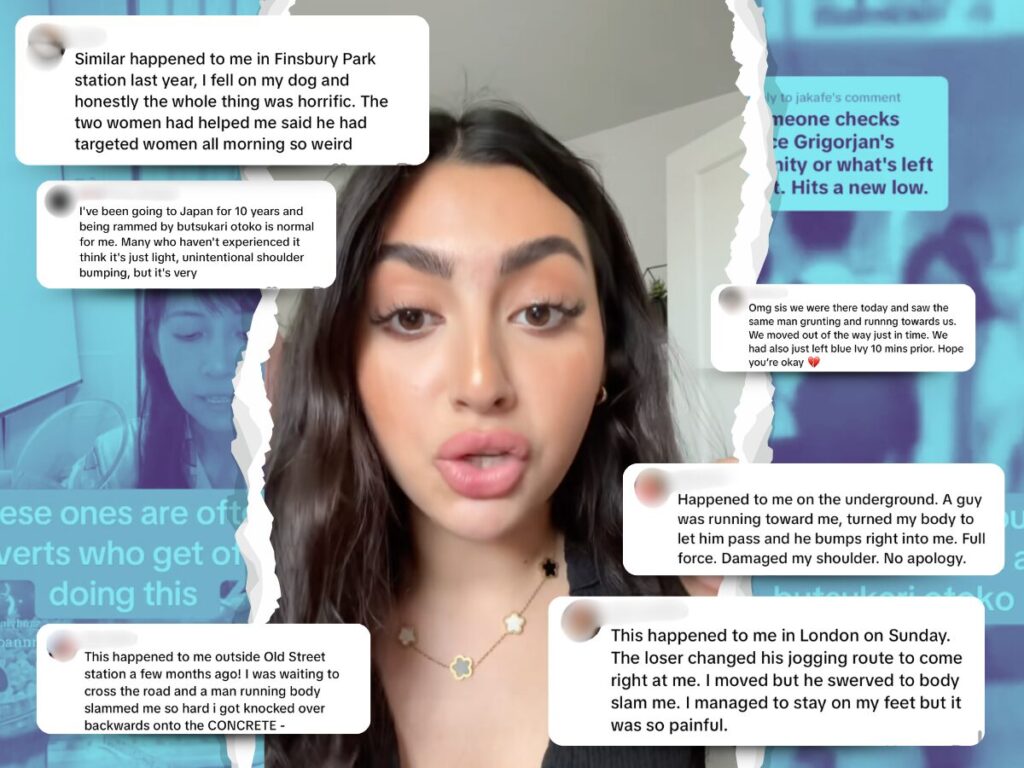

Now, these collisions – sometimes aggressive, sometimes subtle – are surfacing in London. In one viral clip, Ayla Mellek describes being body-slammed to the pavement by a grunting man “twice her size”. Pia Blossom describes a man locking eyes with her before forcing her into a wall. Many of the victims of this assault are certain that they are calculated moments where a woman’s physical presence is tested by a dominating force, rather than a simple accident.

It seems as though butsukari has been exported.

The danger of doubt

Still, many men remain unconvinced. On Reddit, I asked Londoners for their thoughts on stories like Ayla’s. One man insisted: “This could have been an accident, sheer ignorance, or a random bully. But considering his only other suspected victim was an elderly man… it’s a stretch to call it an orchestrated campaign against women.”

Another replied with similar scepticism: “A man bumped into me in Sainsbury’s yesterday. I didn’t stop to ask if he was an incel, so I can’t claim to be a victim of this ‘worrying trend’.”

Here lies the crux of the issue: plausible deniability. Butsukari thrives in the grey area between evidence and interpretation, where the moment is too fast, too casual, and too easy to dismiss. While these men are technically right – not every bump is butsukari – the refusal to believe any might be reveals something deeper. That hesitation, that instinct to doubt until met with incontrovertible proof, is itself part of the violence. It shifts the burden of clarity onto those most destabilised by the act, reinforcing the notion that unless a woman is bruised, broken, or bleeding, she must be exaggerating.

Butsukari is an inherently public act, and as feminist geographer Dr. Rachel Pain puts it, public spaces are “an arena where patriarchal entitlement plays out physically.” In that context, butsukari is about far more than bruises. Every ‘shoulder check’ sends a message to women that many men are unwilling to hear. Your body is secondary. Your presence here is conditional. You are permitted only by my tolerance.

Why naming matters

Some argue that we shouldn’t be so quick to assume intent. That there’s a danger in mischaracterising clumsiness or haste as malice. But we must ask: why is preserving the innocence of men more urgent than acknowledging the harm experienced by women?

Of course, naming carries risk. It can be misused, stretched beyond intent, or dismissed as an overreaction. But that risk must be weighed against the long history of women being ignored, especially when the harm is ambiguous or inconvenient to acknowledge. A 2021 report by the Victims’ Commissioner found that more than half of the women who report domestic abuse feel disbelieved by police. Trust erodes when violence must always be visible to be accepted. In those cases, language is a vessel for recognition, which can transform patterns from anecdote to evidence.

When women like Ayla and Pia speak out, they aren’t calling for every shoulder-checker to face legal consequences. They’re asking to be seen and believed when they say their fear is not imagined. That their injuries (visible or not) are real. By naming these incidents butsukari, we offer coherence in a world eager to dismiss female discomfort as coincidence. We draw boundaries around a pattern that (once seen) is undeniable. A pattern that countless women have called out across Asia and now the UK, after recognising it as a planned and targeted misogynistic act.

If butsukari teaches us anything, it’s that violence doesn’t always arrive with fists. Sometimes, it comes through a shoulder.

So, the next time a woman says she was pushed or slammed on purpose, believe her. Don’t ask if she’s sure. Call it butsukari. Add it to the growing ledger of public violence against women. Because once we name it, we can confront it. And perhaps, in time, we can stop it.